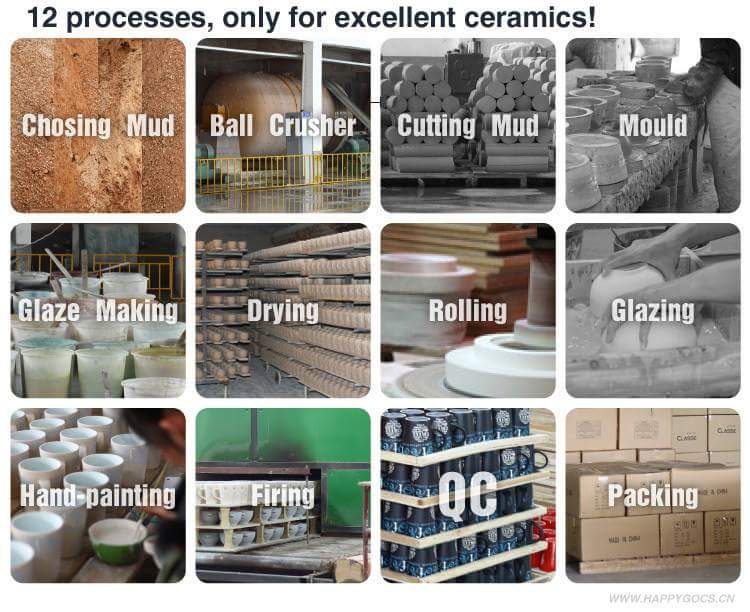

To make porcelain, the raw material

s—such as clay, felspar, and silica—are first crushed using jaw crushers, hammer mills, and ball mills.

After cleaning to remove improperly sized materials, the mixture is subjected to one of four forming processes—soft plastic forming, stiff plastic forming, pressing, or casting—depending on the type of ware being produced.

The ware then undergoes a preliminary firing step, bisque-firing.

[size=16]The Manufacturing Process[/size]

After the raw materials are selected and the desired amounts weighed, they go through a series of preparation steps.

First, they are crushed and purified. Next, they are mixed together before being subjected to one of four forming processes—soft plastic forming, stiff plastic forming, pressing, or casting; the choice depends upon the type of ware being produced.

After the porcelain has been formed, it is subjected to a final purification process, bisque-firing, before being glazed.

The final manufacturing phase is firing, a heating step that takes place in a type of oven called a kiln.

Crushing the raw materials

First, the raw material particles are reduced to the desired size, which involves using a variety of equipment during several crushing and grinding steps.

Primary crushing is done in jaw crushers which use swinging metal jaws.

Secondary crushing reduces particles to 0.1 inch (.25 centimeter) or less in diameter by using mullers (steel-tired wheels) or hammer mills, rapidly moving steel hammers.

For fine grinding, craftspeople use ball mills that consist of large rotating cylinders partially filled with steel or ceramic grinding media of spherical shape.

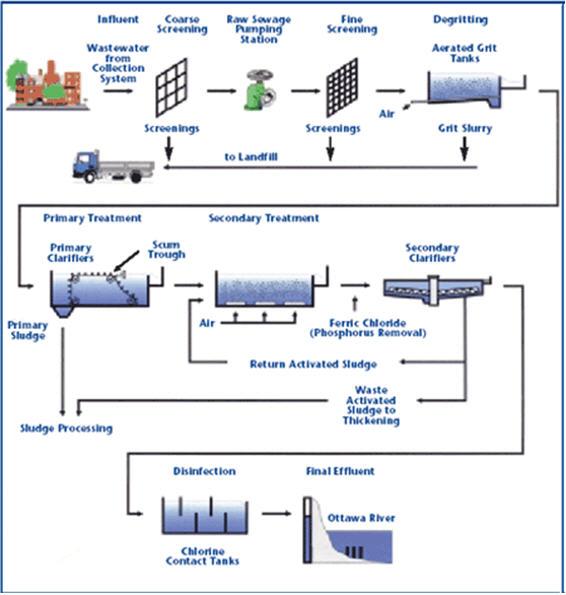

Cleaning and mixing

The ingredients are passed through a series of screens to remove any under- or over-sized materials.

Screens, usually operated in a sloped position, are vibrated mechanically or electromechanically to improve flow.

If the body is to be formed wet, the ingredients are then combined with water to produce the desired consistency.

magnetic filtration is then used to remove iron from the slurries, as these watery mixtures of insoluble material are called.

Because iron occurs so pervasively in most clays and will impart

After bisque firing, the porcelain wares are put through a glazing operation, which applies the proper coating.

The glaze can be applied by painting, dipping, pouring, or spraying. Finally, the ware undergoes a firing step in an oven or kiln. After cooling, the porcelain ware is complete.

an undesirable reddish hue to the body if it oxidizes, removing it prior to firing is essential.

If the body is to be formed dry, shell mixers, ribbon mixers, or intensive mixers are typically used.

Forming the body

Next, the body of the porcelain is formed.

This can be done using one of four methods, depending on the type of ware being produced:

soft plastic forming, where the clay is shaped by manual molding, wheel throwing, jiggering, or ram pressing.

In wheel throwing, a potter places the desired amount of body on a wheel and shapes it while the wheel turns.

In jiggering, the clay is put on a horizontal plaster mold of the desired shape; that mold shapes one side of the clay, while a heated die is brought down from above to shape the other side.

In ram pressing, the clay is put between two plaster molds, which shape it while forcing the water out.

The mold is then separated by applying vacuum to the upper half of the mold and pressure to the lower half of the mold. Pressure is then applied to the upper half to free the formed body.

stiff plastic forming, which is used to shape less plastic bodies.

The body is forced through a steel die to produce a column of uniform girth.

This is either cut into the desired length or used as a blank for other forming operations.

pressing, which is used to compact and shape dry bodies in a rigid die or flexible mold.

There are several types of pressing, based on the direction of pressure.

Uniaxial pressing describes the process of applying pressure from only one direction, whereas isostatic pressing entails applying pressure equally from all sides.

slip casting, in which a slurry is poured into a porous mold.

The liquid is filtered out through the mold, leaving a layer of solid porcelain body.

Water continues to drain out of the cast layer, until the layer becomes rigid and can be removed from the mold. If the excess fluid is not drained from the mold and the entire material is allowed to solidify, the process is known as solid casting.

Bisque-firing

After being formed, the porcelain parts are generally bisque-fired, which entails heating them at a relatively low temperature to vaporize volatile contaminants and minimize shrinkage during firing.

Glazing

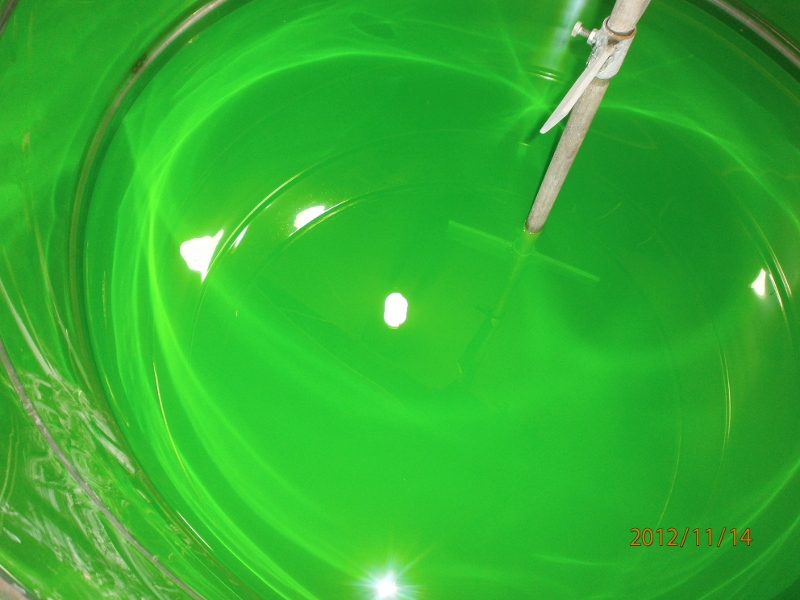

After the raw materials for the glaze have been ground they are mixed with water.

Like the body slurry, the glaze slurry is screened and passed through magnetic filters to remove contaminants.

It is then applied to the ware by means of painting, pouring, dipping, or spraying.

Different types of glazes can be produced by varying the proportions of the constituent ingredients, such as alumina, silica, and calcia. For example, increasing the alumina and decreasing the silica produces a matte glaze.

Firing

Firing is a further heating step that can be done in one of two types of oven, or kiln. A periodic kiln consists of a single, refractory-lined, sealed chamber with burner ports and flues (or electric heating elements).

It can fire only one batch of ware at a time, but it is more flexible since the firing cycle can be adjusted for each product.

A tunnel kiln is a refractory chamber several hundred feet or more in length. It maintains certain temperature zones continuously, with the ware being pushed from one zone to another.

Typically, the ware will enter a preheating zone and move through a central firing zone before leaving the kiln via a cooling zone.

This type of kiln is usually more economical and energy efficient than a periodic kiln.

During the firing process, a variety of reactions take place.

First, carbon-based impurities burn out, chemical water evolves (at 215 to 395 degrees Fahrenheit or 100 to 200 degrees Celsius), and carbonates and sulfates begin to decompose (at 755 to 1,295 degrees Fahrenheit or 400 to 700 degrees Celsius). Gases are produced that must escape from the ware.

On further heating, some of the minerals break down into other phases, and the fluxes present (feldspar and flint) react with the decomposing minerals to form liquid glasses (at 1,295 to 2,015 degrees Fahrenheit or 700 to 1,100 degrees Celsius).

These glass phases are necessary for shrinking and bonding the grains.

After the desired density is achieved (greater than 2,195 degrees Fahrenheit or 1,200 degrees Celsius), the ware is cooled, which causes the liquid glass to solidify, thereby forming a strong bond between the remaining crystalline grains. After cooling, the porcelain is complete.

This transforms not only the colours, but also the glaze, which becomes a solid shiny surface that will survive well for many years.

The gas fired kiln reaches a temperature of 940°-950° C (about 1700° F) in a twenty-four hour cycle, twelve hours to reach the maximum temperature and twelve hours to completely cool.

Only then can we open the kiln and discover the results of so much patient work.

The Manufacturing Process

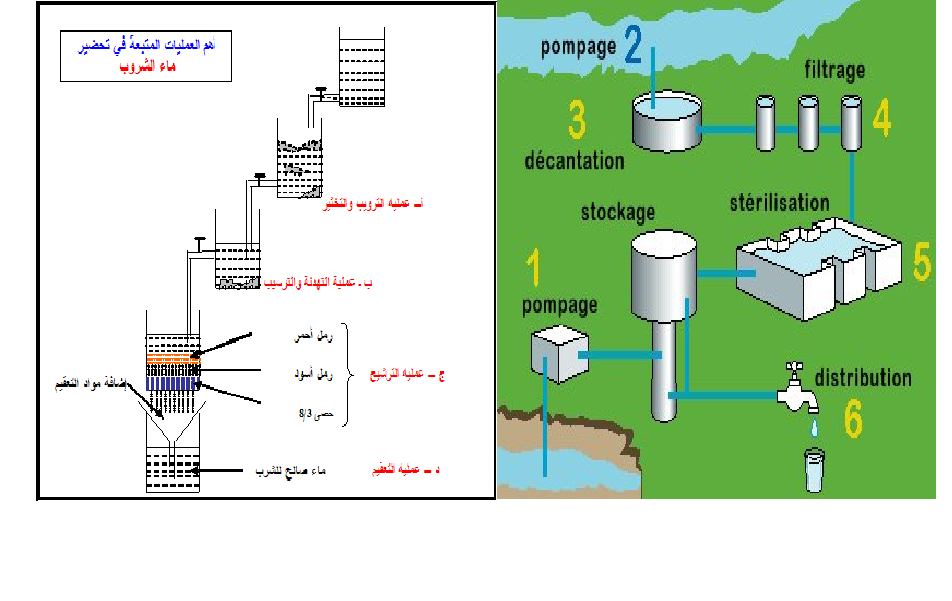

Once the raw materials are processed, a number of steps take place to obtain the finished product.

These steps include batching, mixing and grinding, spray-drying, forming, drying, glazing, and firing.

Many of these steps are now accomplished using automated equipment.

Batching

For many ceramic products, including tile, the body composition is determined by the amount and type of raw materials.

The raw materials also determine the color of the tile body, which can be red or white in color, depending on the amount of iron-containing raw materials used.

Therefore, it is important to mix the right amounts together to achieve the desired properties.

Batch calculations are thus required, which must take into consideration both physical properties and chemical compositions of the raw materials.

Once the appropriate weight of each raw material is determined, the raw materials must be mixed together.

Mixing and grinding

Once the ingredients are weighed, they are added together into a shell mixer, ribbon mixer, or intensive mixer.

A shell mixer consists of two cylinders joined into a V, which rotates to tumble and mix the material.

A ribbon mixer uses helical vanes, and an intensive mixer uses rapidly revolving plows.

This step further grinds the ingredients, resulting in a finer particle size that improves the subsequent forming process.

Sometimes it is necessary to add water to improve the mixing of a multiple-ingredient batch as well as to achieve fine grinding.

This process is called wet milling and is often performed using a ball mill.

The resulting water-filled mixture is called a slurry or slip.

The water is then removed from the slurry by filter pressing (which removes 40-50 percent of the

moisture), followed by dry milling.

Spray drying

If wet milling is first used, the excess water is usually removed via spray drying.

This involves pumping the slurry to an atomizer consisting of a rapidly rotating disk or nozzle.

Droplets of the slip are dried as they are heated by a rising hot air column, forming small, free flowing granules that result in a powder suitable for forming.

Tile bodies can also be prepared by dry grinding followed by granulation.

Granulation uses a machine in which the mixture of previously dry-ground material is mixed with water in order to form the particles into granules, which again form a powder ready for forming.

Forming

Most tile is formed by dry pressing. In this method, the free flowing powder—containing organic binder or a low percentage of moisture—flows from a hopper into the forming die.

The material is compressed in a steel cavity by steel plungers and is then ejected by the bottom plunger.

Automated presses are used with operating pressures as high as 2,500 tons.

Several other methods are also used where the tile body is in a wetter, more moldable form.

Extrusion plus punching is used to produce irregularly shaped tile and thinner tile faster and more economically. This involves compacting a plastic mass in a high-pressure cylinder and forcing the material to flow out of the cylinder into short slugs. These slugs are then punched into one or more tiles using hydraulic or pneumatic punching presses. Ram pressing is often used for heavily profiled tiles. With this method, extruded slugs of the tile body are pressed between two halves of a hard or porous mold mounted in a hydraulic press.

The formed part is removed by first applying vacuum to the top half of the mold to free the part from the bottom half, followed by forcing air through the top half to free the top part.

Excess material must be removed from the part and additional finishing may be needed.

Another process, called pressure glazing, has recently been developed.

This process combines glazing and shaping simultaneously by pressing the glaze (in spray-dried powder form) directly in the die filled with the tile body powder.

Advantages include the elimination of glazing lines, as well as the glazing waste material (called sludge) that is produced with the conventional method.

Drying

Ceramic tile usually must be dried (at high relative humidity) after forming, especially if a wet method is used.

Drying, which can take several days, removes the water at a slow enough rate to prevent shrinkage cracks.

Continuous or tunnel driers are used that are heated using gas or oil, infrared lamps, or microwave energy. Infrared drying is better suited for thin tile, whereas microwave drying works better for thicker tile.

Another method, impulse drying, uses pulses of hot air flowing in the transverse direction instead of continuously in the material flow direction.

Glazing

6 To prepare the glaze, similar methods are used as for the tile body.

After a batch formulation is calculated, the raw materials are weighed, mixed and dry or wet milled.

The milled glazes are then applied using one of the many methods available.

In centrifugal glazing or discing, the glaze is fed through a rotating disc that flings or throws the glaze onto the tile.

In the bell/waterfall method, a stream of glaze falls onto the tile as it passes on a conveyor underneath.

Sometimes, the glaze is simply sprayed on.

For multiple glaze applications, screen printing on, under, or between tile that have been wet glazed is used.

In this process, glaze is forced through a screen by a rubber squeegee or other device.

Dry glazing is also being used. This involves the application of powders, crushed frits (glass materials), and granulated glazes onto a wet-glazed tile surface.

After firing, the glaze particles melt into each other to produce a surface like granite.

Firing

After glazing, the tile must be heated intensely to strengthen it and give it the desired porosity.

Two types of ovens, or

After forming, the file is dried slowly (for several days) and at high humidity, to prevent cracking and shrinkage.

Next, the glaze is applied, and then the tile is fired in a furnace or kiln.

Although some types of tile require a two-step firing process, wet-milled tile is fired only once, at temperatures of 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit or more.

After firing, the tile is packaged and shipped.

kilns, are used for firing tile. Wall tile, or tile that is prepared by dry grinding instead of wet milling usually requires a two-step process.

In this process, the tile goes through a low-temperature firing called bisque firing before glazing.

This step removes the volatiles from the material and most or all of the shrinkage.

The body and glaze are then fired together in a process called glost firing.

Both firing processes take place in a tunnel or continuous kiln, which consists of a chamber through which the ware is slowly moved on a conveyor on refractory batts—shelves built of materials that are resistant to high temperatures—or in containers called saggers.

Firing in a tunnel kiln can take two to three days, with firing temperatures around 2,372 degrees Fahrenheit (1,300 degrees Celsius).

For tile that only requires a single firing—usually tile that is prepared by wet milling—roller kilns

are generally used.

These kilns move the wares on a roller conveyor and do not require kiln furnitures such as batts saggers.or

Firing times in roller kilns can be as low as 60 minutes, with firing temperatures around 2,102 degrees Fahrenheit (1,150 degrees Celsius) or more.

After firing and testing, the tile is ready to be packaged and shipped.

What is Bone China?

Dinnerware terminology can be confusing to the uninitiated. Before learning more about bone china, individuals should learn how it is distinct from other pieces that can have a similar look: fine china and porcelain.

![[MSF+3.jpg]](https://2img.net/h/4.bp.blogspot.com/_SynCnHGx75g/Shl2T3oVhsI/AAAAAAAAAEY/_7oem5pvQ3I/s1600/MSF%2B3.jpg)